It’s not often that we use this space to

talk about developments in the Tax Court of Canada, but a recent case has

brought forward an issue that we end up seeing time and again in personal

injury and family law disputes: real versus declared income.

In Truong v.

the Queen, the

appellant reported annual earnings of around $40,000 from his work as a casting

inspector. After receiving a tip that the appellant was living beyond his

means, the CRA initiated an investigation and learned that he had been convicted

of possession with the intent to traffic marijuana. Clearly, the appellant

elected not to report income from these illegal activities.

Since income was

not reported from these activities, the CRA had to determine the additional

unreported income indirectly from a number of other sources – sadly, the

appellant neglected to keep detailed financial records from his trafficking

business. In determining an appropriate level of income to impute to the

appellant, the CRA examined the income and expenses of his girlfriend – who

could not have financed her personal expenditures without assistance – and real

estate properties held in other individuals’ names, for which evidence existed

that implied the appellant was using them in order to generate rental income.

Imputing Income in Personal Injury Matters

Calculating

damages in personal injury cases is an exercise in weighing possibilities; we

need to ask ourselves realistically, what could the injured have possibly

earned in the absence of their accident? The answer to that question is largely

based on the available evidence, including their background, education,

economic conditions and what is often the most important piece of evidence,

their earnings history.

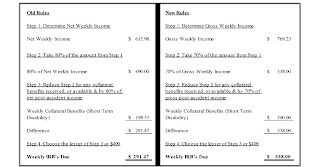

Reported income

is one of the bedrocks upon which a personal injury claim is based. In motor

vehicle collisions, for example, the injured plaintiff is compensated by their

insurer by way of benefits that are based on their income. If this bedrock is

not solid, the injured party stands to lose both their income replacement

benefits in the short-term, and any future damage awards further down the road.

A plaintiff’s personal injury claim without sufficient evidence to establish

their true income is akin to building the proverbial house on a bed of sand.

Individuals from

all stripes will work to minimize their income for tax purposes, using a

variety of strategies ranging over the entire spectrum of legitimacy. Because

it is usually difficult for a salaried employee to minimize their income these

individuals are usually business owners or contractors with the flexibility to

deduct personal expenses and engage in unreported cash business. When we

encounter a client whose income is in dispute prior to being injured, our first

order of business is to develop a case that supports their true earned income.

How do we do

this? It isn’t always possible to construct a purely evidentiary argument;

detailed financial records may not exist. What we will usually end up with is a

scenario based in part on the available financial information and using other,

indirect evidence of additional unreported income. An example will help to

illuminate this process.

Consider a

client that had not reported income for at least five years prior to being

injured in a motor vehicle accident. The client states that he had been working

as a tradesman, but was paid in cash from an employer that also ran an entirely

cash business. He also earned income from other cash sources: renovating houses

in his spare time and purchasing, renovating and then selling homes for a

profit.

Let’s start with

the evidence: we would ask for copies of cheques issued by his employer in

order to corroborate his employment income. In addition, bank statements,

credit card statements or any copies of receipts from home improvement

retailers like Home Depot and other home renovation supply stores would serve

to provide some evidentiary basis for the income that he earned renovating

houses. And finally, mortgage documents and agreements of purchase and sale

would demonstrate a history of real estate income that wouldn’t necessarily

need to be reported for income tax purposes.

Personal cheques

may not be as reliable as a T4, but they are at least indicative of some level

of employment income; receipts and invoices from Home Depot could suggest a

little more than a passing fancy for hardwood floors and granite countertops,

particularly if the expenses are substantial; and mortgage documents are not

only evidence of gains made on buying and selling homes, but they can also be

used to deduce some basic level of income because banks will not lend unless

they can be assured that the borrower has the resources to pay them back.

So, we’ve

managed to cobble together individual pieces of evidence from a number of

sources in order to construct what looks like a picture of this person’s

income. It’s an admittedly fuzzy picture, but the general form is there. The

question we need to ask and answer is, “Is this reasonable?” Let’s say our

analysis resulted in us attributing annual income to our client of about

$40,000, a huge jump from the $0 they claimed for income tax purposes. In light

of that fact, it’s important to take a step back from the details and examine

this scenario we’ve created so that the Courts and we can judge whether or not

our calculations bear any resemblance to reality.

Now, the words

‘reasonable’ and ‘reality’ are a little bit vague in this context, but let’s

agree that it would be neither reasonable nor realistic to impute $100,000 of

income to a single parent living in community housing. If we think about it

this way, a nice way to test the reasonableness of our conclusions would be to

compare our client to his neighbours using statistical data.

So if we were to

summarize the process through which we would impute income to a client that had

previously underreported their income for tax purposes, we could liken it to

penning a novel. The first part – using bills, mortgages, and other pieces of

evidence to construct our argument – is akin to writing the plot. We’re using

little bits of information in order to develop a story about Mr. or Mrs. X and

what they do for a living. The second part – evaluating how they compare to

similar individuals around them – should establish for the reader (read: the

Courts) that this is a work of non-fiction. Our case needs to look more like a

biography than Alice in Wonderland, so it’s important and hopefully evident

that the narrative needs to be consistent and that both parts are integral in

making that happen.

Let the experts at Krofchick Valuations

assist you in creating a case built on a solid foundation. We employ the skills

of forensic economics, business valuations, investigative accounting, and

actuarial science to assist in assessing and quantifying your clients’ economic

position. Let the experts at Krofchick Valuations

help you resolve your case in a timely, efficient, and professional fashion and

see why We Make The Difference.